Battle of Kapyong

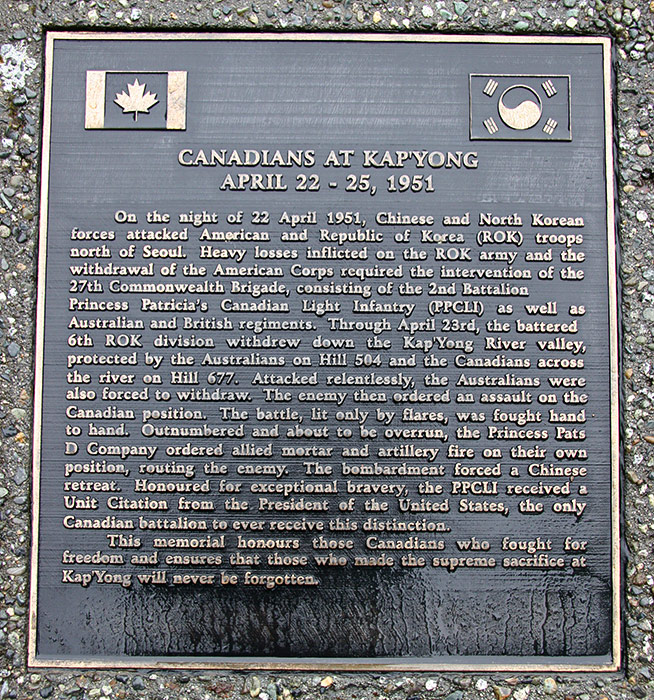

The Battle of Kapyong was a United Nations defensive action fought during the Korean War between April 21-25, 1951.

Battle of Kapyong

The Battle of Kapyong was a United Nations defensive action fought during the Korean War between April 21-25, 1951.

Battle of Kapyong

Prelude to War

From 1910 until the end of the Second World War, Korea had been occupied and ruled by Japan for thirty-five years.

After the Second World War, Korea was split into two administrations, North and South Korea, with the dividing line between them being the 38th parallel. The Japanese surrendered Korea north of the 38th parallel to the Soviet Union, and the country south of the 38th parallel to the United States.

From that point on Korea’s fate was sealed as a country torn between communist and capitalist interests. The Soviets and Americans withdrew from Korea, but they left behind a divided country seething with tension.

That tension erupted on 25 June 1950 when the North Korean Army invaded South Korea. The conflict was to continue for the next three years.

It was the multinational United Nations Security Council’s first test of its mandate to halt the spread of Communist aggression. The Korean War became the first major war that occurred as part of a larger crisis, the Cold War.

During the war, the Republic of Korea (South) was supported by the United States and 21 other members of the United Nations. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North) was supported by China and the Soviet Union.

During the war, UN forces engaged in a bitter struggle with North Korean and Chinese troops to regain control of South Korea. The conflict ended in 1953 with a ceasefire, but a formal peace agreement was never signed.

Today, North and South Korea remain technically at war, separated only by the ceasefire line where the fighting stopped in 1953.

UN Reaction to the War

World reaction to the invasion was swift. At the request of the United States, the Security Council of the United Nations met on the afternoon of the same day, 25 June 1950 and called for immediate cessation of hostilities and the withdrawal of North Korean forces to the 38th Parallel.

As it soon became evident that the North Koreans had no intention of complying with this demand, President Truman ordered the United States Navy and Air Force to support the South Koreans by every possible means.

On the same day, a second UN resolution called on the Members to "furnish such assistance to the Republic of Korea (ROK) as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area". This was, in effect, a declaration of war on North Korea.

On 30 June 1950 President Truman authorized the commitment of American troops. Other UN member nations offered forces and the Security Council recommended that all troops be placed under a single commander.

Thus, a United Nations Command (UNC) was established in Tokyo under General Douglas MacArthur of the United States.

Canadian Reaction to the War

The Canadian Government, while agreeing in principle with the moves made to halt the North Korean aggression, did not immediately commit its forces to action in Korea. At the close of the Second World War the Canadian armed forces had been reduced to peacetime strength and were specially trained for the defence of Canada. Furthermore, the Far East had never been an area in which Canada had any special national interest.

The first Canadian aid to the hard-pressed UN forces came from the Royal Canadian Navy. On 12 July 1950 three Canadian destroyers, the HMCS Cayuga, HMCS Athabaskan and the HMCS Sioux were dispatched to Korean waters to serve under United Nations Command.

These ships supported the assault at Inchon in September 1950 and played an especially important role in the evacuation to Pusan following the Chinese intervention in December 1950.

During the retreat south, a large body of American troops was cut off in the Chinnampo area. The three Canadian destroyers, together with an Australian and an American destroyer, negotiated the difficult Taedong river to successfully cover the embarkation.

Also in July, a Royal Canadian Air Force squadron was assigned to air transport duties with the United Nations. No. 426 Squadron flew regularly scheduled flights between McChord Air Force Base, Washington, and Haneda Airfield, Tokyo throughout the campaign.

On 7 August 1950, as the Korean crisis deepened, the Government authorized the recruitment of the Canadian Army Special Force. It was to be specially trained and equipped to carry out Canada's obligations under the United Nations charter or the North Atlantic Pact.

Canadian Army Special Force

The original components of the Special Force included, the:

- 2Bn Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR)

- 2Bn Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI)

- 2Bn Royal 22e Régiment (R22eR)

- "C" Squadron of Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians)

- 2nd Field Regiment

- Royal Canadian Horse Artillery (RCHA)

- 57th Canadian Independent Field Squadron

- Royal Canadian Engineers (RCE)

- 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade Signal Squadron

- No. 54 Canadian Transport Company

- Royal Canadian Army Service Corps (RCASC)

- No. 25 Field Ambulance, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (RCAMC)

On 8 August 1950, Brigadier J.M. Rockingham accepted command of the Canadian Infantry Brigade. However, following the successful Inchon landings and the UN advances into North Korea during September and November 1950, the war in Korea seemed to be near its end.

Instead of a full brigade, only the 2nd Battalion of the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel J.R. Stone, proceeded to Korea.

However, by the time the troop ship carrying the Patricia’s steamed into Yokohama on 14 December 1950, the battlefront picture had completely changed.

Timeline of War

North Korea Invades: June 1950

The North Korea Army (KPA) crossed the 38th parallel on 25 June 1950 and invaded South Korea. The KPA pushed rapidly southward through the valleys and rice paddies of the Korean peninsula towards the South Korean capital, Seoul, which they occupied on 28 June 1950.

By the first week of August, United Nations and South Korean forces had been pushed south the entire length of the country to the "Pusan Perimeter", a small area in the southeast of the peninsula.

The Inchon Landing: September 1950

UN and South Korean Forces were still holding on when, on 15 September 1950, General MacArthur ordered a daring allied amphibious landing at Inchon, the port of Seoul.

This successful assault, coupled with a breakout from the Pusan bridgehead, changed the military situation overnight. Before long the North Korean troops found themselves on the defensive and were soon in rapid retreat.

The UN and ROK forces moved quickly northward, recaptured Seoul, then crossed the 38th Parallel and advanced north towards the border of Manchuria.

With an apparent victory over the North Korean forces in sight, the United Nations Command failed to notice that the Chinese Peoples Volunteer Army (PVA) had been secretly moving soldiers into North Korea.

China Intervenes: November 1950

In November 1950, as UN forces approached the Yalu River along the border with China, a Chinese Army of over 200,000 soldiers launched a massive offensive against UN and South Korean forces, almost completely destroying the South Korean Army (ROK II Corps) and severely harassing the US Marines forcing another retreat of UN Forces southwards.

By the end of December 1950, UN and South Korean armies had been driven back across the 38th Parallel to positions well south of the Imjin River.

The PPCLI Arrive: February 1951

In this charged atmosphere of unexpected disaster, the emphasis shifted to the speed with which the PPCLI could be thrown into action. The Patricia’s began an intensive training period in the Pusan Perimeter, where they also engaged in actions against guerrilla activities.

A few months later, in February 1951, the 2nd Battalion PPCLI moved north to take its place in the line as part of the 27th Commonwealth Brigade in time to participate in a general UN advance towards the 38th Parallel.

This was a strenuous period for the brigade. The country was rugged, the weather bitterly cold and, although the Chinese were withdrawing northwards, a number of sharp encounters occurred.

In late February the Canadian unit made its first contact with the enemy, and suffered its first casualties in the Korean hills. At the end of March 1951 the Canadians began to move into the Kapyong valley, and by mid-April, the United Nations forces had again pushed north of the 38th Parallel.

On 11 April 1951, General MacArthur was relieved of his command and replaced by Lieutenant-General Matthew B. Ridgway.

The Chinese Spring Offensive: April 1951

By early 1951, it had been suspected for some time that the Chinese were again preparing another large-scale offensive, designed to check the UN advance. It came on 22 April 1951. The engagement which followed, was one of the most severe of the entire Korean campaign.

During the night of April 22nd, Chinese forces struck again. During the attack, the South Korean 6th (ROK) Division, overwhelmed and forced to retreat, was in danger of being cut off and completely destroyed.

The task of the Commonwealth Brigade was to hold open a withdrawal route for them through the Kapyong valley and to prevent deep enemy infiltration.

Although heavily outnumbered, the 2nd PPCLI, the 1st Middlesex Regiment and the 3rd Royal Australian Regiment (RAR) successfully repulsed a massive assault by Chinese Forces at the Battle of Kapyong.

The Battle of Kapyong (April 22-25, 1951)

The Battle of Kapyong began on Sunday, 22 April 1951. It was part of the last major Chinese offensive of the Korean War, the Chinese Spring Offensive, and involved a truly multi-national force facing off against a well-trained and motivated Chinese army in some of the toughest fighting of the war.

The Chinese objective was to recapture the ROK (Republic of Korea) capital of Seoul. Initially they were successful, breaking through the UN front lines 22/23 April. South Korean troops panicked and fled southward leaving behind ammunition dumps, howizters and masses of equipment that could rearm the enemy. The Chinese continued to move down the Kapyong river valley northeast of Seoul.

It was here that Second Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2PPCLI) and Third Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (RAR) dug-in to stop the Chinese advance—2PPCLI on Hill 677 and 3RAR on Hill 504.

In support were two British Battalions, a New Zealand artillery unit, a US tank company and some South Korean troops making this a multinational brigade.

Communist Chinese military philosophy was two-fold, a tactic they had used successfully in their conquest of China.

As Hub Gray described in his book on the battle (Beyond the Danger Close), the Chinese soldiers under these circumstances were effectively, “suicide squads”.

Throughout the night of 23 April and into 24 April 1951, the Chinese 118th Division struck the heavily outnumbered Australians with a series of unrelenting attacks. After eleven hours of fighting, the massive numerical superiority of the Chinese forces made itself felt and the Australians, along with the US 72nd Tank Battalion, were forced to withdraw.

Alone, the 2PPCLI faced the next Chinese assault. By 2200hrs, a hail of tracer bullets lit up the night sky, accompanied by the bugle calls used by the Chinese to signal the start of their attacks.

Totally cut off, 2PPCLI withstood wave after wave of Chinese soldiers swarming forward out of the darkness. As ammunition began to run short, some Patricia’s resorted to using empty rifles as clubs. The Platoon commander (Lt Mike Levy) through the Commander of “D” company (Capt Mills) was forced to call in an artillery barrage on his own position to keep it from being overrun.

The morning of April 25th found 2PPCLI still holding its ground. Following an air drop of more ammunition and support from British troops advancing from the south, the Chinese were forced to retreat having sustained heavy casualties.

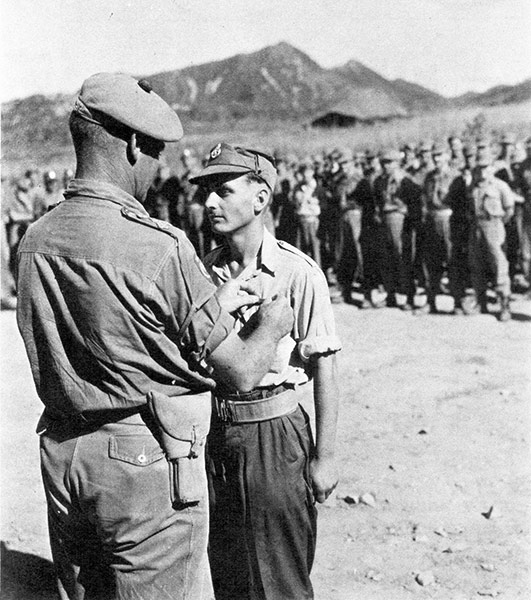

The gallant stands of the Second Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and the Third Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment merited special recognition from the US President.

President Truman conferred The Presidential Unit Citation on both battalions and “A” Company from the US 72nd Tank battalion that provided support during the Battle. 2PPCLI is one of only two Canadian units to ever receive this award.

UN Counterattacks: May - October 1951

A last engagement by UN Forces during the summer of 1951 pushed the Chinese Forces back across the 38th Parallel. A stalemate ensued, and for the next two years little ground changed hands. The war of movement was replaced by static warfare of trenches, minefields and barbed wire.

Although ceasefire negotiations began in July 1951, fighting continued along the front in short but intense battles, while both sides jockeyed for advantage. During this time the front line hardly moved. Negotiations continued between the two sides for two more years, until on 27 July 1953, a ceasefire agreement was finally reached.

Truce Talks Begin

Early in July 1951, at Communist instigation, ceasefire negotiations were begun near Kaesong on the 38th Parallel. These truce talks ran into difficulties at the outset and the suspicion prevailed that they were never intended by the Communists to produce an early peace, but were being used to gain military advantage.

As the negotiations dragged on, the bloody fighting continued along the front lines. The Canadian brigade became part of the newly formed British Commonwealth Division, the first of its kind in history. It spent the long Korean summer engaged in patrolling the region of the Imjin River.

During September and October the Commonwealth troops fought to protect the supply route to the Chorwon River, and pressed across the lower Imjin to attain better defensive positions. The line, which was finally established, remained relatively unchanged until the end of hostilities two years later.

In October and November the Chinese launched another series of attacks. In one engagement against the Royal 22e Régiment the focal point was Hill 355, an important feature which dominated most of the divisional front. During the night of November 23-24, 1951 the R22eR, were attacked several times after heavy shelling, but no ground was lost, even when one of their forward platoons had been dislodged and another surrounded.

As ceasefire negotiations were renewed, orders were given on November 27 that no further fighting patrols were to go out and that artillery action was to be restricted to defensive fire and counter-bombardment.

However, as the enemy continued to shell and send out patrols these restrictions were gradually lifted. From the winter of 1951-52 until the end of hostilities, a period of static warfare set in. It became a war of raids and counter-raids, booby traps and mines, bombardments, casualties, and endless patrolling.

A system of rotation for Canadian units began with the relief of the 2nd PPCLI by the 1st Battalion in November 1951. In April 1952 the 1st Battalion Royal Canadian Regiment and 1st Battalion Royal 22e Régiment replaced their second battalions, and Brigadier M.P. Bogert took command. "B" Squadron, Lord Strathcona's Horse, replaced "C" Squadron in June, and other units of the original force were similarly rotated.

A second rotation began with the arrival of the 3rd PPCLI in November 1952, followed in 1953 by the 3rd RCR, the 3rd R22eR, and "A" Squadron of the Strathcona's and other replacement units. Brigadier J.V. Allard became Canadian commander in the theatre until 1954 when Brigadier F.A. Clift succeeded him, in turn, at the time of the final Canadian rotation.

As the fighting continued on into 1953 under the name of the "Twilight War", defences on both sides grew stronger and deeper. Canadians engaged in patrolling and ambush with the object of dominating "No Man's Land" and securing prisoners. But while negotiations for a peaceful end to the conflict continued, the fighting and stalemate dragged on.

The Fighting Ends

Fighting in Korea finally came to an end when the Korea Armistice Agreement was signed at Panmunjom on 27 July 1953. It must be appreciated that every phase of the Korean campaign was a combined operation in which United Nations forces on the sea and in the air played a prominent and vital role. Without naval supremacy and air power the land campaign would have been virtually impossible.

The fact that Korea is a peninsula offered unusual scope for naval support. In providing that support a total of eight ships of the Royal Canadian Navy joined their UN and ROK navy colleagues, performing a great variety of tasks.

They maintained a continuous blockade of the enemy coast; prevented amphibious landings by the enemy; and supported the United Nations land forces by the bombardment of enemy-held coastal areas and attacks by carrier-borne aircraft. In addition, they protected the friendly islands and brought aid and comfort to the sick and needy of South Korea's isolated fishing villages.

Although Canada was unable to provide fighter squadrons to the United Nations, 22 Royal Canadian Air Force pilots served with the American units. They were on exchange duty with the US Fifth Air Force and flew with Sabre-equipped fighter-interceptor squadrons. Altogether 26,791 Canadians served in the Korean War and another 7,000 served in the theatre between the ceasefire and the end of 1955. United Nations forces (including South Korean) fatal and non-fatal battle casualties numbered about 490,000. Of these 1,558 were Canadian. The names of 516 Canadian war dead are inscribed in the Korea Book of Remembrance.

The truce, which followed the armistice of 27 July 1953, was an uneasy truce, yet the UN intervention in Korea was a move of incalculable significance. For the first time in history an international organization had intervened effectively with a multi-power force to stem aggression and the UN emerged from the crisis with enhanced prestige.

The PPCLI in Korea

Three Battalions from the Patricia's fought in Korea—2nd and 3rd Battalions recruited especially for that purpose. Although the 2nd Battalion saw some of the fiercest fighting in Korea and were the first to go over, 1st and 3rd Battalions also served under severe and challenging circumstances during later rotations.

At the end of the Second World War, Canada’s infantry had reverted to just three battalions—the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, the Royal Canadian Regiment and the Royal 22e Régiment. The decision by the Department of National Defence to convert these three Active Force battalions to a Mobile Strike Force of parachutists saw the Patricia's as the first to complete their transformation to an airborne battalion by the spring of 1949.

With the invasion of South Korea by North Korea in June 1950, the Canadian government decided to fulfill their commitment to send a fighting force to Korea by raising three new Battalions from volunteers. These new volunteers would be attached to the existing Active Force regiments as the 2nd Battalions. Initially called the Canadian Army Special Force, they were later renamed 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group.

By the summer of 1950, members of 1PPCLI were training the new recruits of 2PPCLI for Korea. In the fall of 1950 those men surplus to the 2nd Battalions were formed into 3rd Battalions and all were sent to Fort Lewis near Tacoma, Washington to complete training.

However, by November 1950 it looked like a UN victory was assured as the North Koreans had been pushed back after a daring landing at Inchon by the US marines—the North Korean army had virtually collapsed. As it looked like the mission had turned into a prolonged occupational duty, it was decided to only send over 2PPCLI while the rest of the 25th Brigade continued their training at Fort Lewis.

But by the time 2PPCLI landed in Pusan, 18 December 1950, massive numbers of Chinese troops had attacked and the whole picture had changed with a UN defeat looming again. 2PPCLI would make their infamous stand at Kapyong a few months later in April 1951.

After Kapyong, in May 1951 the rest of the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade arrived in Korea and in July 1951 the Canadians joined the rest of the Commonwealth forces to form the 1st Commonwealth Division. Along with four other divisions, the Commonwealth Division drove across the Imjin River in Operation Commando on 3 October 1951 to establish a new UN defensive front line—Jamestown Line.

Most of the original Special Force volunteers in 2PPCLI rotated back to Canada beginning mid October 1951 and were replaced by 1st Battalion. 1PPCLI stayed in Korea until they were relieved by 3PPCLI in November 1952.

The character of the Korean War changed after 2PPCLI went home as the new UN frontline—Jamestown Line—was as far forward as the UN troops were allowed to go. Under UN mandate, Korea was not fought to obtain a victory but was a limited war fought to regain the status quo existing before the Communist invasion.

Therefore, the Korean War became a defensive war for the UN troops—a war of waiting and attrition where both sides patrolled no-man’s land, raided each other’s positions and once in a while wrested a hilltop or portion of a ridge from the enemy.

The Chinese liked to attack at night nullifying UN air power and artillery strength. The men were plagued with illness and disease incubated in the hot, muggy summers and extremely cold winters. This static warfare continued to drag on for 2 years even after armistice talks resumed at Panmunjom 15 October 1951.

In November 1952 3PPCLI took over 1PPCLI’s positions on the Jamestown Line. There they had a relatively quiet tour from November 1952 until July 1953 when the Korean War ended with the signing of the Korea Armistice Agreement at Panmunjom. The truce was an uneasy one and Korea remains divided to this day.

Casualties and Honours

More than 3,800 Patricia’s served in Korea; 429 were wounded, 107 killed and 1 taken prisoner of war. Today, Kapyong and Korea are two of 22 Battle Honours emblazoned on PPCLI’s Regimental Colours.

After 12 months on active service, 3 PPCLI was reduced to nil strength on 8 January 1954. The Commanding Officer, RSM and selected officers and men transferred to the 2nd Battalion, Canadian Regiment of Guards to form the nucleus of the new unit.

This ended the Korean War era which saw the birth and disbandment of the 3rd Battalion. It was another 16 years before the 3rd Battalion was re-born.