Robert Allan Barr

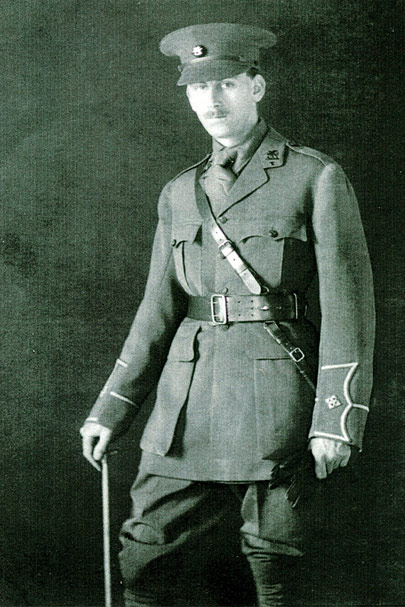

Allan Barr served in England and France with the British Army, first as a cadet in the Artists’ Rifles and then as a Lieutenant in the 1/1st Monmouthshire Regiment.

Robert Allan Barr

Allan Barr served in England and France with the British Army, first as a cadet in the Artists’ Rifles and then as a Lieutenant in the 1/1st Monmouthshire Regiment.

Robert Allan Barr

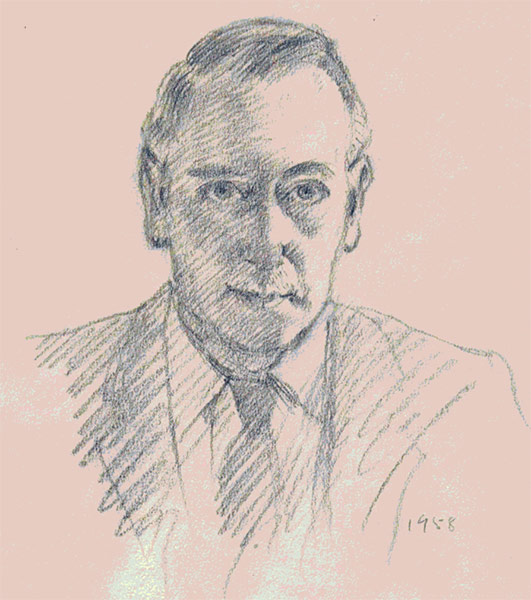

Robert Allan Barr (1890—1959) was a young aspiring artist with works exhibited at the Royal Academy, the Paris Salon, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal Society of Oil Painters, all by the age of 22.

But then the First World War broke and Allan, along with his two brothers, volunteered for service.

Allan served in England and France with the British Army, first as a cadet in the Artists’ Rifles and then after nine months preliminary training he was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the 1/1st Monmouthshire Regiment and immediately proceeded to France. His first engagement was near Poperinghe on the Ypres front where severe casualties were sustained from a gas attack.

While fighting in the trenches he witnessed the horrors of war as few of us can imagine. Later he reported to H.Q. 46th (North Midland) Division at Lucheux serving under Lt. Col. W.J.M. Freestum, Somerset Light Infantry and later as Aide de Champ to General Thwaites and General Boyd.

At the end of the war Allan returned to England in March 1919. In his diary he stated “and so the war ended for me—or so I thought at the time, but now I know that no war ever ends”. The Second World War started only 20 years later.

After the war, Allan Barr returned to his passion of portrait painting. He married Margaret Seccombe in November 1921, and emigrated to Canada a year later. Together they raised a family of four children, Thomas James, Margaret Elizabeth (Moffat), Christopher John and Robert Allan.

A Soldiers Story

Although unknown in athletic circles save as a keen English rugby fan, Allan once threatened the world’s fastest sprinter. During the war, Allan’s commanding officer of the 1st Monmouthshire Regiment selected Barr to go forward in the trenches and make a map of the front line. Barr was perhaps chosen because of his keen artistic talent.

Barr went forward, without enthusiasm, he admitted, and commenced his peaceful war-time trek. The quiet which heralds disaster prevailed. Barr increased his speed and cut down on technique, but he wasn’t half through when the German guns commenced a little barrage for his personal edification. The picture in the making was not of Allan Barr’s inspiration and the taps from the trenches were becoming more frequent and demanding.

"They clearly indicated that they wished me to desist and vacate", related Allan. "So I did with dispatch. I tore down the road as barren of shade trees as the Sahara, and I travelled faster than any human before or since. But the Germans were neat pacers. Every few yards when my feet did touch the ground there was a shell landing right behind me. I knew I could never make it.

Every minute was my last. They could have hit me a dozen times but they always landed a little behind and when I finally dove into a hole at the end of this forced marathon and got my wind, I realized that the German sense of humour had asserted itself on my behalf. They had obviously let me off because they had had so much fun chasing me". Allan Barr

Gas in the First World War

The painting for this panel is dedicated to the soldiers of the First World War who endured the gas attacks that were so common during that conflict.

In spite of the Hague Convention of 1907 outlawing the use of poisonous gas during warfare, the Germans chose to unleash this new and deadly weapon against the Allies in April 1915. The weapon they chose was chlorine, an asphyxiating gas. Released from ground canisters, it killed thousands of unsuspecting Commonwealth soldiers in their trenches and crippled thousands more.

After this German precedent, the British began using poison gas as well. However the rapid adoption of gas masks took away the element of surprise and meant that gas would never again be decisive in battle.

Many different types of gas were used during the First World War including phosgene and the deadly mustard gas, which gas masks would not protect against. By the end of the war, it is estimated that as many German as Allied soldiers had become casualties through the use of this terrible new weapon. Gas was never used again as a weapon in Europe.