Curley Christian

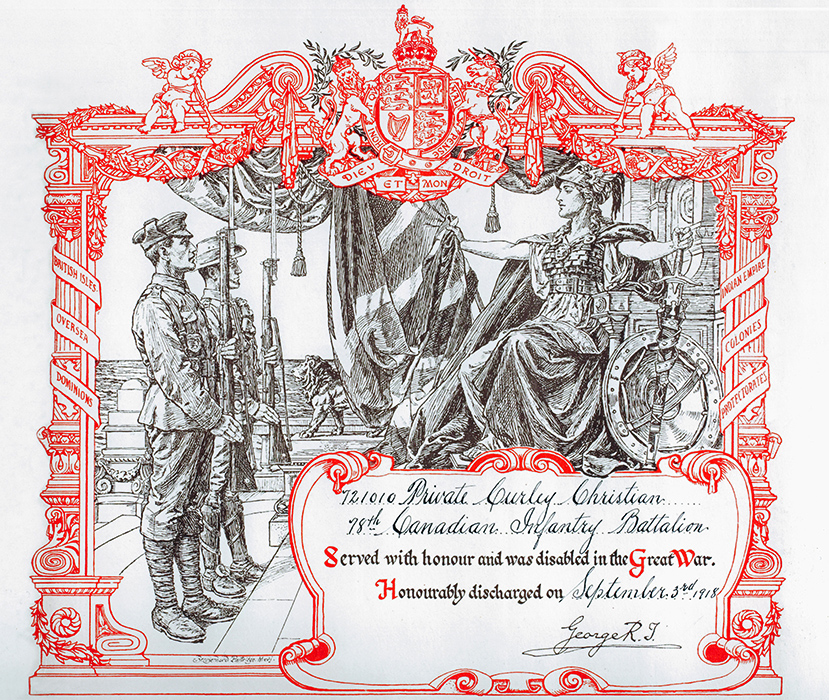

Ethelbert "Curley" Christian served in the Canadian army with the 78th Battalion, also known as the Winnipeg Grenadiers.

Curley Christian

Ethelbert "Curley" Christian served in the Canadian army with the 78th Battalion, also known as the Winnipeg Grenadiers.

Curley Christian

Curley Christian lost both his arms and legs to amputation after gangrene set in after he was hit by a German artillery shell during the Battle of Vimy Ridge, in April 1917. Nineteen years later, in 1936, he and many other Canadian veterans returned to Europe for the unveiling of the Vimy Ridge memorial.

By this time, Curley had reached such a high level of acclaim that prior to the event, King Edward VIII had a special wheelchair provided for him. Curley lived to the ripe old age of 69, and became one of the best known members of the Canadian War Amps Association.

The explosion crushed all four of his limbs and he lay on the battlefield for two days before he was found. The doctors expected him to die, but against the odds he somehow managed to survive. Curley became the only quadrilateral amputee to survive the First World War.

Curley Christian

Apparently, only one quadrilateral amputee survived the First World War, an African American who fought in the Canadian army. His name was Ethelbert "Curley" Christian.

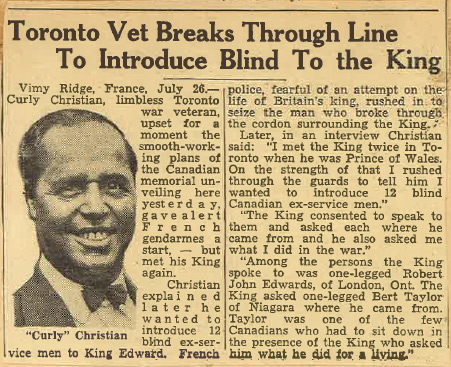

Curley lost his arms and legs in combat at Vimy Ridge, France, in 1917. He was expected to die, But 19 years later, he and other Canadian veterans returned to Europe for the Vimy Ridge Reunion in 1936.

They met King Edward VIII in London, and at Vimy Ridge, they watched him unveil the tall stone memorial to Canada.

"The king even provided a special wheelchair for Curley," said Sharon Williams, Christian's great-great cousin.

Born in Homestead, Pa., in 1884, Christian lived to age 69. He spent almost half his life beating the odds. "Doctors made bets on his recovery, and lost," explained his 1954 obituary in the Toronto Telegram. "They were wrong again back home later when they told him he would never wear artificial limbs."

Williams, a police dispatcher in West Hartford, Conn., has collected newspaper and magazine clippings about her ancestor who moved to Canada before the First World War. He was 31 when he joined the Canadian Army in 1915.

He parents named him Ethelbert Christian. He made "Curley," a childhood nickname, his permanent name.

Christian fought in the 78th Canadian Infantry Battalion. Also known as the Winnipeg Grenadiers, they were in the Canadian Corps of the British army.

Christian defies the odds

On April 9, 1917, the Canadians attacked the Germans at Vimy Ridge, a strategic 4 mile-long rise near the town of Vimy. After 3 days of fierce combat, the Canadians seized the blood-soaked high ground.

More than 3,500 Canadians perished at Vimy Ridge. Another 7,000 were wounded, including Christian.

German artillery almost killed him on the first day of the battle, Williams said. "He was blown up in a Canadian trench. Debris crushed all four of his limbs, and he lay on the battlefield for 2 days before he was found barely alive."

When a pair of soldiers bore him away on a stretcher, German shells again rained on the blasted trench. "The two men who were carrying him were killed instantly," Williams said. "Curley had survived once more."

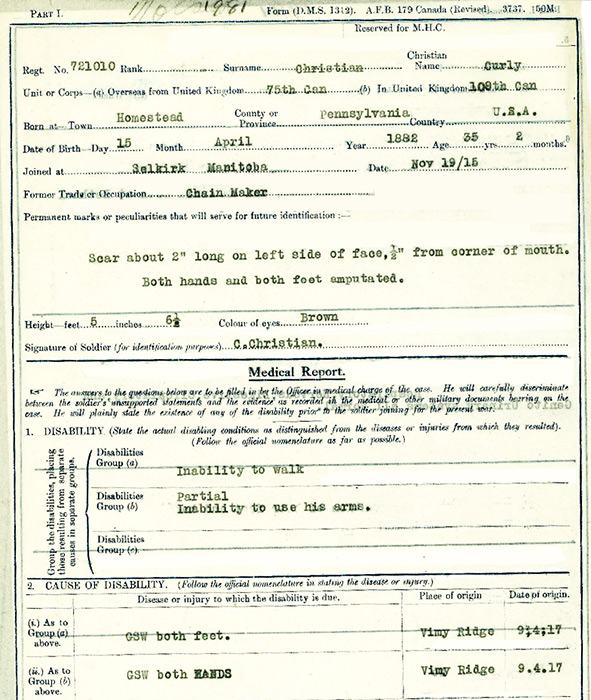

Christian ended up in a French army hospital. "Gangrene had set in and the doctors had no choice but to amputate all four of his limbs," Williams said. They cut off his arms below the elbows and his legs below the knees.

It seemed unlikely that Christian would recover from so drastic an operation, Williams added. "He heard one of the nurses say she wished be would die because she could not imagine him having any kind of life without arms and legs."

The morning after Christian's four infected limbs were removed, the nurse heard a patient lustily singing "It's a Long Way to Tipperary," a popular solider song from the First World War. It was Curley.

"When she walked up to his bed, he looked up at her, gave her a great big smile and said, ‘Hi, I'm still alive,'" Williams explained. "That smile became his trademark."

Curley Returns Home Christian was sent back to Canada in September 1917. His journey home across the Atlantic was on the hospital ship, the Llandovery Castle, which was tragically sunk by a German submarine eight months later on June 27th, 1918.

At Christie Street Hospital in Toronto, he fell in love with Cleo MacPherson, a volunteer aide from Jamaica. They got married in 1920, made Toronto their home, and reared a son, Douglas Christian, who became a Canadian sailor in the Second World War.

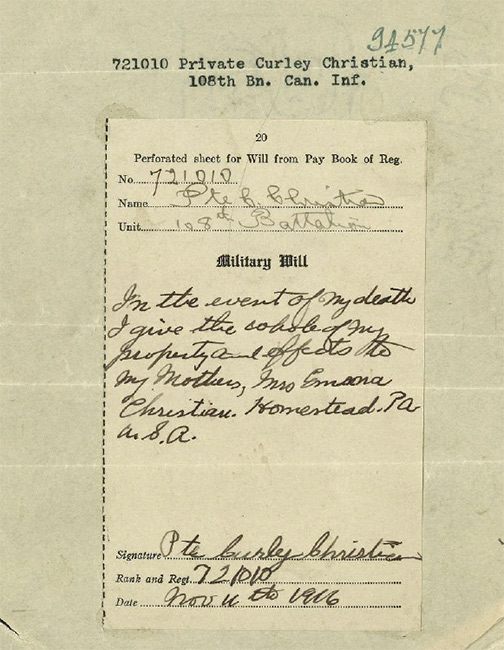

Curley's service records

Attendance Allowance started

Curley and Cleo Christian helped ensure that other seriously disabled veterans could stay in their own homes, according to a video program from the War Amps of Canada. The Private, non-profit organization offers bilingual services to amputees – civilian and military – across the country.

In the video, Cliff Chadderton, a Second World War amputee and War Amps chief executive officer, explained how the Christians' inspired Canada's Attendance Allowance program. He said that Christian wanted to go home from the hospital and that his wife said she could attend to his needs.

However, Cleo Christian also told the hospital director they were not wealthy people and that somehow or other, the government had to pay some money for this. The director liked her idea; after all, Christian's hospital stay was "costing the government a fair amount of money," according to Chadderton.

The hospital head pronounced Mrs. Christian's proposal "a good financial deal." Thus, according to Chadderton, "they turned around and they said let us put something in called Attendance Allowance. And what it really means is that the seriously disabled can stay in their own homes, and if they do, is addition to pension, the government will pay an additional amount. And that was the origin of Attendance Allowance."

Meanwhile, Christian did so well with his new prosthetic legs that "it was hard to tell that the reason for his limp was so serious," the Telegram said. He astonished "all who saw him – including many orthopaedic specialists" with how deftly he used his mechanical "hands," the paper also reported.

"He could feed himself with a knife and fork he made himself", Williams said. "They could be inserted into the wrists of his prostheses." Using a clip attached to his artificial arms, "he could write a legible script, either right or left handed," the Telegram said.

Christian, who became a Canadian citizen, was one of the best-known members of the Amps Vets, an association of servicemen who had lost limbs. "His smile and outgoing personality were legendary in the Amp Vets," Williams said.

The Telegram reported that Christian "was a permanent fixture at the annual Amps' Conventions, missing few." But "his greatest thrill," the paper added," was attending the Vimy Reunion of 1936."

Christian remained eternally positive

Even so, Christian's "irrepressible cheerfulness was not a meaningless Pollyanna attitude," the Telegram cautioned. "If I thought I could grow another set of legs and arms by griping, I would gripe," he said once. "Only the amps themselves know how we feel," the paper also quoted Christian as saying.

Nonetheless, Christian was unfailingly kind to people who did not understand his disability, the Telegram said, again quoting incidents like the time a woman chided him for taking too long to remove his hat for the Canadian National Anthem. "Perhaps you would take it off for me," the newspaper said he replied. "You see, I lost both arms fighting for the King."

Another of Williams' newspaper clippings tells about a letter Christian wrote to Private First Class Robert L. Smith, a U.S. Soldier who lost his arms and legs in the Korean War. Christian told Smith, who was also from Pennsylvania, that rehabilitation was "not a question of bravery, but a question of facing the situation. It is a matter of looking forward, not back."

He also advised the 20-year-old Smith, "If you have got any worries about girlfriends, scrap them. I did not meet my wife Cleo until 1920 and she took me as I was – no arms or legs. We have been the happiest couple in the nation."

However, Christian counselled the soldier, "be wary of sympathy" and "have patience and a sense of humour. But the greatest secret is to know, and to know for sure, that God will take care of you. What He has done for others, He will do for you."

From an article written by Berry Craig for the O&P Business News

Curley Christian's Scrapbook

During and after the Vimy Ridge Reunion in 1936, Curley's wife Cleo, collected a vast amount of memorabilia from the trip which she subsequently put into a scrapbook.

After both Curley and Cleo passed away, the whereabouts and even the existance of the scrapbook was forgotten. After a friend of Curley's son Douglas passed away, his wife discovered the scrapbook by chance in their attic while cleaning up.

The scrapbook was eventually given to Curley's grand-daughter, Sharon Williams who treasured it "like stepping back into the past". It was loaned to The Military Museums in 2012.

Highlights from Curley and Cleo's scrapbook from the Vimy Ridge Reunion in 1936 are shown below.

Read more: Black Canadians in Uniform