The Battle for Ortona

In December of 1943, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division was ordered to capture the port city of Ortona on the Adriatic coast of Italy.

The Battle for Ortona

In December of 1943, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division was ordered to capture the port city of Ortona on the Adriatic coast of Italy.

The Battle for Ortona

It took the Canadians seven days to take possession of this picturesque town in what became known as the bloodiest battle of the Italian Campaign.

For the Canadians it was a bitter struggle, the town was heavily defended and soldiers moved from house-to-house by blowing holes in adjoining walls; an innovative technique that was dubbed "mouse-holing".

Today, the town has been completely rebuilt but the evidence of war remains visible on many of the buildings. Shell holes and artillery damage can be found on old stone walls and foundations that were not cleared away yet used as a foundation for the new town.

In the main square a faded stencil reads "Allied Troops Curfew 2100 Hours". Canadian Veterans returning to Ortona are greeted with tears of gratitude by those who remember the liberation, in spite of the devastation and loss.

"It wasn't hell. It was the courtyard of hell. It was a maelstrom of noise and hot, splitting steel... the rattling of machine guns never stops... wounded men refuse to leave, and the men don't want to be relieved after seven days and seven nights... the battlefield is still an appalling thing to see, in its mud, ruin, dead, and its blight and desolation."

These were the words of CBC news reporter Matthew Halton during the battle of Ortona in December 1943. Dubbed the Italian Stalingrad, the battle of Ortona pitted the 1st Canadian Division against Germans of the elite 1st Parachute Division in what was to be one of the Second World War's most brutal examples of urban combat.

Prelude to Battle

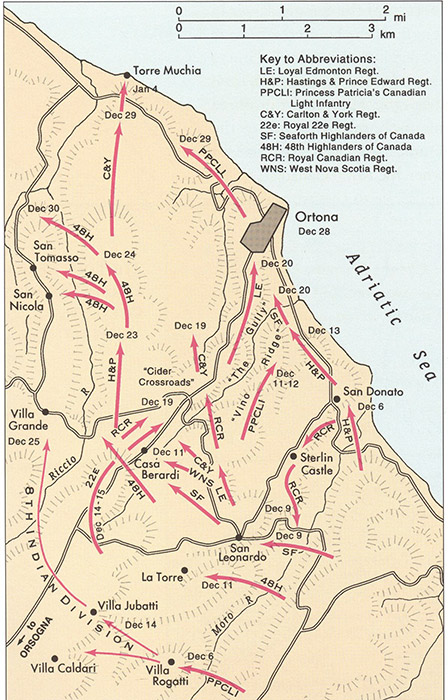

In December 1943 the British 8th Army, which included the 1st Canadian Corps, was fighting its way up the Italian peninsula towards Rome. By the 4th of December the Canadians stood on the south side of the Moro River at the eastern end of the vaunted Gustav Line, a series of strongly held German positions stretching across the Italian Peninsula.

Major General Chris Volkes, the division’s new commander, was tasked with crossing the Moro and capturing the small port of Ortona two miles behind it. Facing the Canadians were Field Marshal Albert Kesselring's crack 90th Panzer Grenadier Division and 1st Parachute Division, positioned along a strong line based on the Ortona-Orsogna road and with orders to hold to the bitter end.

With the bridges destroyed by the Germans, General Volkes ordered two brigades across the Moro on the evening of 5th. The attacks proceeded without any artillery support in order to achieve maximum surprise. The attacking 1st and 2nd Brigades met with stiff German resistance and fierce counterattacks, and by nightfall of the 6th only one battalion from the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment held a bridgehead on the north bank.

Three days of heavy fighting followed as Canadian troops moved across the river towards the town of San Leonardo, always in the face of fierce German counterattacks and by the 9th the bridgeheads across the river were secure and the 1st Division continued its move north.

The Gully

The next obstacle to be overcome was a gully running just south of the Ortona – Orsogna road. This tiny geographic feature was fortified by the retreating Germans and turned into a formidable obstacle. The landscape was by this point a muddy quagmire, saturated by rain and thick with mines.

After frontal assaults proved useless, the Royal 22e Regiment and a squadron of Ontario Regiment tanks managed to flank the German line and capture Casa Berardi. It was during this action that Captain Paul Triquet of 'C' Company won Canada's first Victoria Cross in the Mediterranean.

Remembered by his battle cry: "Ils ne passeront pas" (they shall not pass), Triquet and his small group spent the night defending their position from continuous German counter attacks.

Yet, even outflanked, the Germans refused to budge from the Gully. To finally dig them from their positions the fire of 13 artillery regiments was unleashed in a massive barrage dubbed "Morning Glory."

This deluge of shellfire hit the German line on the morning of the 18th and in two days of heavy fighting they were forced to withdraw, the Royal Canadian Regiment finally reached the crossroads and the road to Ortona was open.

The Battle

The Canadian division wasted no time moving on the city. On December 20th the Loyal Edmonton Regiment moved up from the crossroads towards the town. Waiting in Ortona were German Paratroopers, a fiercely loyal group of soldiers ready to fight for every house and street.

The town of Ortona, like many old European cities, consisted of tall buildings and narrow lanes, often with connected cellars. The Germans improved this ready-made defensive position further by blocking and mining the streets. In Ortona every house could be a pillbox and every pile of rubble a strongpoint.

For the next week the Canadians engaged in a fearsome struggle to wrest control of the city from its German defenders. The Allied superiority in airpower and artillery was nullified as the Germans took shelter in any number of basements or hastily dug out fortifications. The two forces were often locked so closely together that it would have been difficult to know where to bomb or shell in any case.

To avoid German ambushes and killing zones, the Canadians started "mouse-holing" through buildings – blasting their way through walls rather than using the streets. This innovative technique along with the 75mm guns of the Three Rivers Tank Regiment allowed the Seaforths and the Edmonton Regiment to claw their through to the centre of the city and capture the Piazza Municipale, where the Germans had originally hoped to funnel Canadian infantry into propositioned machine guns.

Ortona was primarily a battle of infantry, where the rifle and high explosive became more valuable than the dive-bomber or artillery piece. The Canadian infantry took Ortona, quite literally, house-by-house and street-by-street.

Often fighting from the top floor down, they would secure a room and then move down the stairs tossing grenades to clear the way. When the Germans turned houses into strong points that proved too costly to take, they were simply blown up with TNT or anti-tank guns.

It was in Ortona that the Canadians wrote the book on urban combat. The only break in the fighting came on December 25, 1943 when both Canadian Regiments treated their men to Christmas dinner in the Church of Santa Maria di Constantinopoli. Each rifle company was pulled from the lines for two hours in succession to enjoy a bit of good food, music and celebration in the mist of battle.

Soon after Christmas the Germans recognized how untenable their position had become; their lines of communication and supply were threatened by the advancing Canadians and their losses had become horrendous. On the evening of the 27-28th the paratroopers surrendered what ground they had left and withdrew to the north.

The cost of taking Ortona was high. The Canadian Army had taken nearly 2,400 casualties in the month of December and for a while the 1st division was effectively taken out of the war to reorganize and bind its wounds. The German Army took equally heavy losses and for days Ortona remained littered with German dead.

Ortona was won not through airpower or material superiority; it was the victory of the average Canadian. Here the Canadian soldier had pitted his skill and courage against some of the best soldiers in the Wehrmacht and won. Two of Hitler's finest divisions were broken and forced to retreat while the Allied advance up the Italian Peninsula continued.

The Story of Paul Triquet, VC

In December 1943, near an Italian farmhouse outside Ortona, a Québécois officer led his men against fierce German resistance to earn the Commonwealth's highest military honour.

Amid the din of exploding shells and small arms fire, the sight of both sides' casualties scattered across the battlefield, and the unmistakable smell of cordite thick in the air, French-Canadian Acting Major Paul Triquet momentarily lowered his weapon.

The men of 'C' Company, the Royal 22e Régiment – nicknamed the 'Van Doos' – joined their commanding officer. So, too, did the enemy troops they faced.

Nearby, the burning husk of a Panzer Mk. IV, a German tank destroyed a short time before, crackled and buckled under immense heat. Otherwise, an unsteady silence descended over the Italian countryside, so close and yet so far from the coastal town of Ortona.

Safe passage had been granted to a woman and her two children. Dashing between the opposing forces, the family successfully made it to the Canadian line.

It had been a brief respite, a fleeting moment of humanity in an increasingly brutal and attritional war. Almost as quickly as it had arrived, the moment was gone.

Triquet raised his weapon once more and, with comrade and enemy alike, pulled the trigger.

The 33-year-old Québécois soldier knew that the day, 14 December 1943, had only just begun. Unbeknownst to him then was that he would soon earn the Victoria Cross.

Duty, Not Glory

Born into the French-Canadian community of Cabano, Quebec, on 2 April 1910, Paul Triquet had long understood the realities – and often true cost – of military service.

'He was a young child during the First World War,' explained John MacFarlane, historian and award-winning author of Triquet's Cross: A Study of Military Heroism. 'His father (Florentin) was a French citizen who was involved in the 1914-1918 conflict. Paul saw his father volunteer, recognizing that it was related to a sense of duty, not glory.

'Florentin was a victim of a gas attack – as so many were – and he suffered when he came home. His whole family was aware of that. So, in witnessing his father's struggles, Triquet saw serving as more of a sacrifice than a way to gain recognition.'

The lessons Paul had learned were promptly put to the test during the 1918 influenza pandemic. At just eight years of age, the boy became a messenger between the local priest and doctor, visited affected families, and transported food supplies to those in need.

Having developed his own sense of duty, it was perhaps inevitable that Paul Triquet – the product of his family's strong military roots over generations – would find his place in the Canadian armed forces. In 1925, aged 15, he tried to enlist in the army only to be rejected for being underage. Success came in 1927, albeit after lying that he was 19 years old.

The French-speaking recruit had overcome the first hurdle, yet many more awaited him in the predominantly anglophone environment of Canadian military service.

'Because he was a Francophone at that time,' said John MacFarlane, 'he didn't know a lot of English. He was determined to continue learning the language, accepting the obstacles and adapting himself. But he was well aware that not everyone would do that.'

'Triquet took it upon himself to translate some of the course materials, including manuals. He created a French-English dictionary of military terms, which was sorely needed. It was informal but quite well done, and it was helpful to younger Francophone recruits.'

'Most important was his recognition that it was a problem. Triquet proposed realistic solutions so that when war came, French-Canadian recruits were in a better position.'

Such had been Triquet's remarkable initiative, combined with his adeptness as a training instructor, that he had risen through the ranks to sergeant major by October 1936.

Unfortunately, his personal life had not been as successful as his military career. In 1938, Triquet became legally separated from his wife, Alberte Chenier, whom he'd married several years previously, and lived apart from his two children, son Claude and daughter Yolande.

Nevertheless, by September 1939, war had finally come – and duty called.

Culture Shock

Departing Canada within three months, Paul Triquet and his Royal 22e Régiment arrived in the United Kingdom on 18 December 1939. There, in a country increasingly paranoid about spies and espionage, the challenge of a language barrier took on an entirely new guise.

It was a culture shock to say the least. Notably in one instance, Québécois Major P.E. Poirier was arrested by local authorities suspicious about his accent.

Generally, however, the French Canadians settled into their usual routine of training and preparation for battle, a wait that would prove longer than anticipated.

In the meantime, Triquet turned his attention to becoming a commissioned officer. The arduous process involved training in Britain and back in Canada. Not until 7 October 1941 was the newly promoted lieutenant ready to return to his beloved Van Doos.

Disaster met other Canadian forces in Hong Kong and Dieppe, but the wait continued for Triquet and his men over the subsequent years. That changed in July 1943 with the invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky). By that stage, the Royal 22e Régiment – and 1st Canadian Division overall – had been attached to British Eighth Army for the campaign ahead.

Though the Van Doos remained in reserve for the initial Allied landings in Sicily on 10 July, the Canadians would soon have ample opportunity to showcase their fighting spirit.

The cost of that spirit was arguably evident in Triquet's rapid promotions over the ensuing weeks. On 30 July, the lieutenant became officer commanding 'C' Company at the rank of acting captain. Mere days later – on 5 August – he was again elevated to acting major.

All the while, Triquet was proving himself a capable, if ordinary, commander.

'He had experience leading from very different roles, and his men respected him,' said MacFarlane. 'He was also leading by example of discipline, but he wasn't reckless.

'He wasn't taking unnecessary risks. He was following his orders, and he was determined to encourage his men to carry out the orders and nothing more, but nothing less.'

The Long Road to Ortona

Duty, always, had defined Triquet's military service, and he had been fairly consistent throughout. Yet with Sicily in Allied hands and with Anglo-American planners looking towards mainland Italy, he was about to face his greatest test of all.

First Canadian Infantry Division landed on 3 September 1943 as the entire British Eighth Army began advancing north up the boot. In response, the German defenders engaged the Allies in a fighting retreat – intent on making them pay for every inch of ground.

Enemy resistance increased in ferocity, casualties rose, and the weather worsened during November and into December. Arriving at the south bank of the Moro River, Major-General Chris Vokes instructed his 1st Canadian Division to gain a foothold on the far side.

A three-pronged attack kickstarted the campaign on the night of 5-6 December. Despite moderate success on the far flanks, capturing the village of San Leonardo proved a horrendous ordeal for the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada without armour support. Only on the 9th were the opposing 90th Panzergrenadier Division fully dislodged.

Already, securing the long road to Ortona had been a bloody affair, and a considerable obstacle still remained. That obstacle had been dubbed 'The Gully,' a 197-feet-deep (60-metre) and 262-feet-wide (80-metre) natural trench spanning five kilometres (three miles). This daunting geographical feature, perhaps unsurprisingly, was a defender's paradise.

Thrusting his men forward in repeated direct assaults, Major-General Vokes became known as 'The Butcher' when eight of his nine battalions were blunted in their efforts to seize The Gully over 10-13 December. That left the Van Doos with the next attack – an unenviable task if ever there was one, not least because of recent changes to the enemy defences.

Then unknown to Allied authorities, a fresh unit of elite German paratroopers had arrived on the battlefield. Meanwhile, Paul Triquet and his 'C' Company, together with a squadron of Ontario Regiment tanks, would lead the Royal 22e Régiment into the fray on the 14th.

Their initial objective: slicing a wedge toward an Italian farmhouse called Casa Berardi.

Allied artillery opened fire at 0600 hours, the bombardment so relentless and intense that even some of Triquet's understrength unit appeared shaken. Nevertheless, at 0730 hours, the French-Canadian officer ushered his 81 men forward to an uncertain fate.

Almost immediately, 'C' Company met a platoon of Germans all too happy to surrender. Triquet sent them back to the Canadian line as the Van Doos pushed on.

Their objective but a short distance away, no one was surprised when a German Panzer Mk. IV lurched into action. The enemy armour was promptly joined by a maelstrom of machine gun and mortar fire, yet far worse was the absence of Canadian tanks to counter the threat.

Unfortunately, the Ontario Regiment's seven Shermans were far behind wading through a muddy quagmire. The supporting 'D' Company was likewise engaged elsewhere. Triquet's 'C' Company, at least for now, was alone.

A PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank) team attempted to silence the deadly Panzer only for the weapon to malfunction. Thankfully, a second PIAT was called up in time to destroy the tank – albeit not without the Canadians sustaining casualties in the process.

It was then that a short-lived silence swept over the battlefield. It was then that the Italian family scurried past debris and bloodied bodies. It was then that Paul Triquet and 'C' Company fired anew, determined to capture Casa Berardi and beyond.

Leading from the Front

After several hours of relentless fighting, and with 'C' Company's numbers whittled down to approximately 50, the Van Doos were still a mile away from the farmhouse.

Recognizing their perilous circumstances, Acting Major Triquet attempted to encourage his beleaguered men with words that would later become famous: 'We are surrounded, the enemy is in front, behind and at our sides – the safest place is the objective.'

The Canadians charged ahead with the since-present armour support of Major 'Snuffy' Smith. During the advance, Triquet repeatedly clambered atop the tank commander's Sherman to direct fire at concealed positions, often dropping gravel through the open turret to get attention before pointing at the target. Slowly, steadily, the combined force gained ground.

Finally, at around 1500 hours, Casa Berardi and the surrounding buildings fell to the Van Doos. No more than 14 fit and able men of 'C' Company, along with four Shermans, were now tasked with defending against the inevitable German counterattack.

Enemy snipers, tanks and mortars were a constant source of harassment. Ammunition and other essential supplies were also running dangerously low. Worse, the effectiveness of Allied artillery had been hampered by the death of the forward observation officer.

While the arrival of 'B' Company helped relieve pressure, there remained a desperate need for additional reinforcements. Triquet anxiously awaited 'D' Company under his friend Major Ovila Garceau as the nearby Germans hurled insults and invitations to surrender.

At 0300 hours the next day, 15 December, Major Garceau and his men found their way to the Canadian defenders at Casa Berardi. 'Never in my life would I feel an emotion as strong as the one I felt hearing in the dark the voice of my best friend, with his company, bringing reinforcements to our small, exhausted group,' recalled Triquet of the moment.

They would need every solder they could get for what lay ahead.

The Van Doos mobilized at 0600 hours for an attempt on their second objective, a junction on the Ortona-Orsogna road codenamed the Cider Crossroads. Despite artillery support and the infantry's best efforts, the position proved temporarily out of reach. Thus, the decision was taken to fall back to Casa Berardi for 48 hours and await further reinforcements.

Now down to just 79 troops in all four companies, Triquet spent the rest of the 15th leaping from shell hole to shell hole as he tried to maintain spirits. 'This continual movement was very important for my men and even more so for me' he later recalled. 'In the state of mind I was, seeing all those dead bodies strewn over the area, and being unable to bury them, I had to, in order to hang in there, be able to speak with the few survivors that remained.'

The anticipated reinforcements, including seven tanks and, hours later, some 100 personnel 'Left out of Battle' (LoBs) filtered through to Casa Berardi from midnight over 15-16 December. They brought with them supplies of water, rations, arms and ammunition.

More bloodshed followed when daylight broke. The since bolstered Canadians themselves, however, refused to break – in part due to their ever-inspirational commander.

MacFarlane explained: 'Triquet just kept motivating and rallying the troops. He wasn't just leading from the back. He was leading from the front.'

Fatigue nevertheless caught up with Triquet over the night of 16-17 December. While examining a P-38 pistol he had captured as a trophy, the officer accidentally discharged it and narrowly missed his friend, Captain Bernard Guimond. Shortly thereafter – and likely much to Captain Guimond's relief – it was mutually agreed that Triquet needed some rest.

The Québécois soldier slept for the next 24 hours, seemingly and understandably oblivious to the world as the fighting raged on around him. Another attempt was made to capture the Cider Crossroads on 18 December, but again the men were denied the objective. Not until the next day, 19 December, did the well-defended junction fall into Canadian hands.

The battle for Casa Berardi was over, even if the urban battle of Ortona was only just beginning. It had come at an extraordinarily high price; of Triquet's originally 81-strong 'C' Company, a mere nine had still been fit and able by the end of the engagement.

Each and every Canadian defender had showcased remarkable valour and resilience against terrible odds. Each and every sacrifice, no matter the circumstances, deserved recognition. Yet in the eyes of Allied authorities, there could be only one Victoria Cross recipient.

That representative: Paul Triquet, V.C.

An Ordinary Soldier

The Moro River Campaign in its entirety, from the bridgehead to The Gully to Casa Berardi to Ortona (the latter liberated on 28 December), would ultimately become one of the most recognizable contributions made by the Canadians during the Second World War.

One of the most recognizable faces, meanwhile, would be Paul Triquet. On 6 March 1944, it was announced that the French-Canadian officer had earned the Victoria Cross for 'magnificent courage and tireless devotion to duty', as his citation reads.

The news came at a pivotal juncture in Canadian politics, not least because Triquet was, at the time, the conflict's sole Canadian V.C. recipient available for public relations (Dieppe Raid V.C. holder Cecil Merritt was a prisoner of war, while others hadn't been announced).

Thrust onto the stage to promote Canada's war effort over the subsequent months, Triquet found himself enduring a new battle unlike any he had experienced before. It would prove to be a great challenge for a soldier wishing nothing more than to be back with his men.

MacFarlane explained the complex motivations behind Triquet's PR tour: 'The most obvious thing is he was a Francophone, showing French Canadians that they were involved in the war and doing well. But it was also probably more showing to Anglophones that French Canadians were involved and doing well. So, it helped the government in both ways.

'He was presented the way heroism was seen at the time as superhuman,' continued MacFarlane. 'He wasn't a regular guy doing a good job, he was a demigod. Combined with his PTSD, carrying the weight of being a demigod became an added burden.'

Triquet participated in the Sixth Victory Loan Campaign to help drive war bond sales, but the desire to return to active service remained. He was later granted his wish of being reunited with the Van Doos, although for PR and training purposes rather than as a combatant.

'From a young age,' said MacFarlane, 'Triquet saw military service as something based on discipline and following orders. You don't decide which battles you're going to fight. You're told what to do and you do your best. So he accepted it even if he was very uncomfortable.'

Over the years – and against the backdrop of various speaking events and press interactions – the heroic story of Paul Triquet became increasingly skewed against his wishes.

Words were put into his mouth he'd never said. The efforts of his comrades were likewise all but erased from the narrative. Even his personal life was warped by reports that he was a committed family man – something Triquet himself would concede not to be true.

Developing anger and drinking problems, the Québécois V.C. recipient became too much for the military to handle and, in 1947, he was effectively forced to retire.

It was during his time as a civilian that military heroism – and what it represented – underwent an evolution. MacFarlane said: 'It was increasingly accepted that [Triquet] wasn't superhuman or a demigod. He had faults, and it was becoming increasingly obvious that he had faults, and he didn't have the same pressure to be perfect moving forward.'

Triquet eventually overcame his issues well enough to join the Canadian Reserve Force. There, bolstered by his beloved military family, he once more rose through the ranks to become a brigadier-general until relinquishing his command with honour in 1959.

The military, without the incessant speaking events and war bond drives, and, above all else, without the demigod status, was a place where Triquet could feel at home. When he passed away on 4 August 1980 at the age of 70, the perceived hero of Casa Berardi had never fully settled into his fame. Instead, Triquet embraced his Victoria Cross for the inspiration it could provide to his men – as well as for those buried beneath Italian soil just outside Ortona.

'Triquet was an ordinary soldier,' said MacFarlane. 'He was the perfect embodiment of the ordinary soldier, but at a time when he was not allowed to be ordinary.'