The Boer War

The South African War (1899-1902) or, as it became known, the Boer War, marked Canada's first official dispatch of troops to an overseas war.

The Boer War

The South African War (1899-1902) or, as it became known, the Boer War, marked Canada's first official dispatch of troops to an overseas war.

The Boer War

In 1899, fighting erupted between Great Britain and the two Boer republics, the Orange Free State and the South African Republic. These states, settled by descendants of the region's first Dutch immigrants, were formed in the mid 1850's as a result of long-standing tensions in southern Africa between the British and the original Boer settlers.

The discovery of mineral wealth in the region awakened British interest in the region and sparked the descent into war between the British and the Boers. The Boers were not expected to survive for long against the world's greatest power. Pro-Empire Canadians nevertheless urged their government to help.

While many English-Canadians supported Britain's cause in South Africa, most French-Canadians and many recent immigrants from countries other than Britain wondered why Canada should fight in a war halfway around the world. Concerned with maintaining national stability and political popularity, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier did not want to commit his government. Yet the bonds of Empire were strong and public pressure mounted. As a compromise, Laurier agreed to send a battalion of volunteers to South Africa.

Over the next three years, more than 7,000 Canadians, including 12 women nurses, served overseas. They would fight in key battles from Paardeberg to Leliefontein. The Boers inflicted heavy losses on the British, but were defeated in several key engagements.

Refusing to surrender, the Boers turned to a guerrilla war of ambush and retreat. In this second phase of fighting, Canadians participated in numerous small actions. Gruelling mounted patrols sought to bring the enemy to battle, and harsh conditions ensured that all soldiers struggled against disease and snipers' bullets.

Imperial forces attempted to deny the Boers the food, water and lodging afforded by sympathetic farmers. They burned Boer houses and farms, and moved civilians to internment camps, where thousands died from disease. This harsh strategy eventually defeated the Boers.

Of the Canadians who served in South Africa, 267 were killed and are listed in the Books of Remembrance. The Canadian government claimed at the time that this overseas expedition was not a precedent. History would prove otherwise. The new century would see Canadians serve in two world wars, the Korean War, and dozens of peacekeeping missions.

Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry

On 3 October 1899, with war imminent, the British government suggested that Canada could provide men for service in South Africa. These would be absorbed individually into British battalions or regiments, thus overcoming the inexperience of the Canadians.

Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier and the Québec wing of the Liberal Party were opposed to providing troops but, on the outbreak of war on 11 October 1899, a wave of enthusiasm in English Canada forced their hand. After two days of Cabinet deliberations, Canada offered eight 125-man units, a total of 1,000 men, all volunteers.

Recruiting began on 14 October, with each of the eight units being raised at different centres across the country in order to obtain national representation. Each company included a core of professional troops from the tiny Permanent Force, augmented by volunteers enlisted for six months' service, which could be extended to 12 months if necessary.

Meanwhile, the government sought to assure a strong Canadian identity for the contingent by changing its offer to a single "regiment of infantry, 1,000 strong." When Great Britain agreed to this arrangement later in October, it was a straightforward matter to combine the eight smaller units into a larger formation of 1,019 officers and men. They became the 2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry (RCRI), (now the Royal Canadian Regiment), the only infantry component of the Permanent Force at the time.

Unlike the regional units of the part-time militia, however, the RCRI represented the whole nation, and it could permanently carry the battle honours from South Africa after 2RCRI had completed its tour of duty and disbanded. Members of the Permanent Force made up about fifteen percent of the total strength of the unit, and this included the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel William Dillon Otter.

When the battalion arrived in South Africa on 29 November 1899, after an uncomfortable month-long sea voyage, it was still a fighting unit in name only. Lieutenant-Colonel Otter estimated that a third of the battalion was without prior military service, and half the men were no better than recruits.

The battalion was able to train during the two months it spent on lines-of-communications duties after it arrived in South Africa. During this period there were a few opportunities to see action, including the assault on Sunnyside kopje on 1 January 1900, in which C Company, and the machine gun section, participated alongside British and Australian troops.

On 12 February 1900, the battalion joined the 19th Brigade to march and fight in the great British offensive aimed at capturing Pretoria, the capital of the Transvaal. The Royal Canadians (as 2 RCRI was often referred to at the time) were soon in action at Paardeberg Drift, suffering heavy casualties on 18 February, and mounting the famous attack that led to the surrender of General Cronje's Boer forces on the 27th. Paardeberg was the first major British victory of the war.

After Paardeberg the battalion fought in the British advance on the Boer capitals of Bloemfontein and Pretoria, gaining in experience and reputation all the while. By the time 2 RCRI marched past Lord Roberts in Pretoria on 5 June 1900, it was considered by many observers as good as any battalion in the British Army.

Unfortunately, Canadian arrangements to replace losses from battle and disease were totally inadequate and by this time the battalion was at less than half strength. With the Transvaal capital in British hands, and the war seemingly won, the RCRI took up lines-of-communications duties once again. The unit spent the rest of its tour of operations on this assignment, except for an interlude spent with a column of infantry chasing mounted Boer forces.

The 2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry had set a very high standard for the Canadian units that followed it on active service in the South African War.

The Royal Canadian Dragoons

Canada's first contingent, the Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry, had barely sailed for South Africa when, on 2 November 1899, the Canadian government offered a second contingent consisting of horse-mounted infantry and field artillery. At first, Britain declined Canada's offer, believing there was no need for additional troops.

However, London changed its mind in mid-December after a series of disastrous defeats at the hands of the Boers. In raising the new mounted unit, the Canadian government searched for men who were already experienced horsemen and good shots.

The unit was originally named the 1st Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles, and comprised a total of 19 officers and 371 men and their horses, organized into two squadrons. The core of each squadron was provided by experienced regular officers and men from the Royal Canadian Dragoons, the cavalry unit of the Canadian Permanent Force.

For this reason, in August 1900, at the unit's own request, the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles were renamed the Royal Canadian Dragoons. The volunteers comprising the remainder of the battalion came from cities and towns in Manitoba and the eastern provinces. Many were members of cavalry regiments of the part-time militia.

The battalion disembarked at Cape Town on 26 March 1900 and was soon on its way to the front to join the 1st Mounted Infantry Brigade. The Dragoons fought a number of engagements in the advance to Pretoria, and subsequently participated in operations on the high veldt east of that city.

In one of these, at Leliefontein on 7 November 1900, a detachment from the unit, with two 12-pounder field guns of "D" Battery, Royal Canadian Field Artillery, fought off a series of mounted charges by a superior Boer force. Three Dragoons won the Victoria Cross for this action.

A number of factors contributed to the success of the Royal Canadian Dragoons. First, its voyage to South Africa was delayed by a month because of sickness in the crew of the troopship. This allowed the unit to train properly before its dispatch into battle.

Secondly, in addition to some very fine soldiers and a popular and spirited commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel François-Louis Lessard, the unit also possessed more than its share of brave and able officers who led from the front – a trait reflected in battle casualties of two killed and four wounded among the ten lieutenants.

Unlike most other units, moreover, the Dragoons used their machine gun section very aggressively. The Royal Canadian Dragoons was, in fact, perhaps the most effective Canadian unit to serve in South Africa, and among the best on either side.

Canadian Mounted Rifles

The North-West Mounted Police, with some 750 personnel, could field more trained mounted men than the regular army. L.W. Herchmer, commissioner of the force, offered to raise a unit of "hand picked police, ex-police and cowboys" to fight in South Africa.

Ottawa accepted his offer when it decided to raise a second contingent for overseas service. The new unit recruited at North-West Mounted Police posts across the western territories in what are now the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta. Members of the police filled thirteen of the twenty officer positions, and made up roughly forty percent of the other ranks.

The battalion was originally named the 2nd Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles (CMR), but this was later changed to the 1st Battalion, CMR. The unit arrived at Cape Town on 27 February 1900, the day that the Boers surrendered at Paardeberg.

Despite concerns that the war would end before the unit saw action, in March and April, it took part in the expedition to suppress a rebellion by Boers in the western Cape Colony before joining the march to Pretoria and beyond.

While the battalion did well, it was hampered to a certain extent by changes in the ranks of its senior officers caused by battle casualties and the departure of the commanding officer, North-West Mounted Police Commissioner Herchmer, whose health broke down. He was replaced by Lieutenant-Colonel T.D.B. Evans, an officer from the Royal Canadian Dragoons. The battalion nonetheless distinguished itself on a number of occasions, and earned a reputation for aggressive scouting.

Royal Canadian Field Artillery

The brigade division of artillery in Canada's second contingent grouped together three batteries. Each battery consisted of three sections, each of two 12-pounder breech-loading guns. The 12-pounders, however, were outranged by the Boers' field guns. Despite this handicap, the Canadian gunners more than held their own during operations in South Africa.

The batteries were designated "C", "D", and "E", to signal the brigade division's link to the Permanent Force's "A" and "B" Batteries, Royal Canadian Field Artillery. There was, in fact, a core of permanent force artillery personnel in each battery. Additional members came from militia field batteries. "C" and "D" Batteries' militia gunners came from units in Ontario, and also from Winnipeg; "E" Battery's came from units in Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.

"D" and "E" Batteries arrived in Cape Town in February 1900 and participated in the suppression of the Boer rebellion in the western Cape Colony. "C" Battery, on its arrival in March 1900, went north to Rhodesia to join the Rhodesian Field Force, which then moved south to the relief of besieged Mafeking. The three batteries then continued to operate separately; even sections within each battery often acted independently with different forces, in some cases being detached for months at a time. The brigade division was only reunited at the end of its tour of duty and return to Canada.

Although usually out of the limelight, the three batteries saw much action. A section of "D" Battery particularly distinguished itself at the battle of Leliefontein.

Strathcona's Horse

On 10 January 1900, Lord Strathcona, the Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, offered to raise a regiment at his own expense for service in the British Army in South Africa. The Imperial authorities accepted his offer and thus was born one of the more unusual regiments of the South African War.

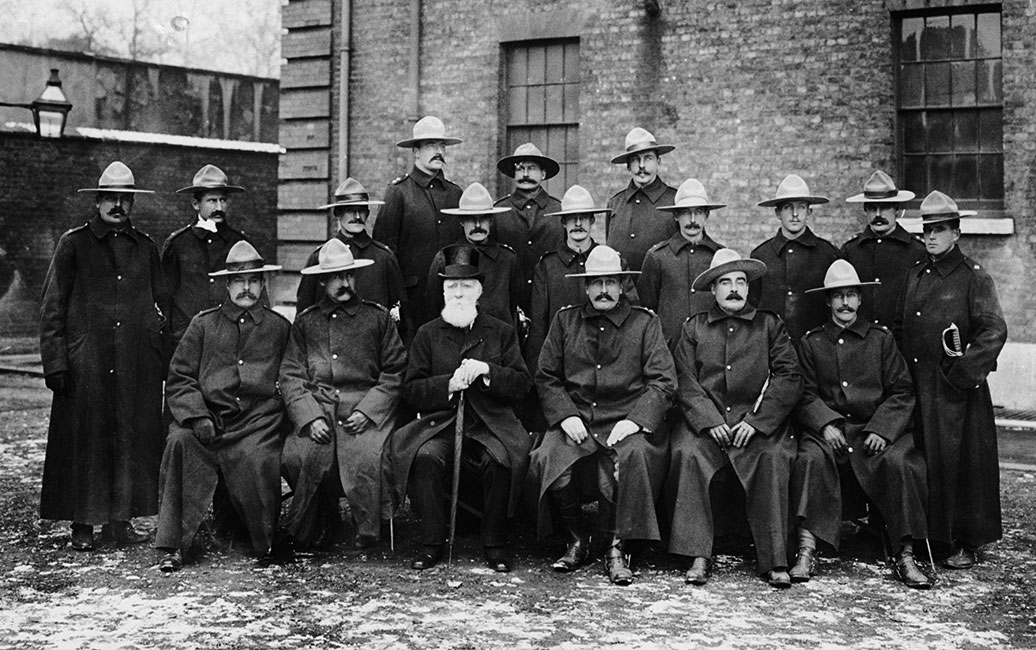

While officially a British unit, the distinction was lost on the Canadian public, politicians, and the men serving in its ranks. It could hardly have been otherwise, as the unit was recruited entirely in the Canadian West. It was equipped by the Canadian government, quartered in Lansdowne Park, Ottawa, and paraded on Parliament Hill. The men cut impressive figures, resplendent in wide-brimmed Stetsons, and mounted on cow ponies with western saddles and lassos.

The unit was known as Strathcona's Horse. It was made up of three squadrons recruited in Manitoba, the territories that would later become the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, and British Columbia. A cadre of mounted police joined Strathcona's Horse, among them the commanding officer, the legendary Superintendent Sam Steele.

Strathcona's Horse arrived in Cape Town on 10 April 1900, and was delayed there by an outbreak of disease among its horses. Finally, in June, the regiment joined General Buller's Natal Field Force and took part in the clearing of the Boer forces from that colony, and also in operations intended to link up with the main army in the Transvaal. On 5 July, at Wolve Spruit, a member of the unit, Sergeant Arthur Richardson, won the Victoria Cross for rescuing a wounded comrade.

The regiment experienced a considerable amount of hard fighting during the remainder of its tour of operations. In January 1901, the Canada-bound unit stopped in London where the new monarch, King Edward VII, personally presented its members with their South African campaign medals, while Lord Strathcona proudly looked on.

10th Canadian Field Hospital

The third Canadian contingent was the only one to take a field hospital with it to South Africa. The 10th Canadian Field Hospital (10 CFH), which departed Canada in January 1902, was quite small; numbering only 61 in all ranks and 29 horses. It was organized into a hospital staff of five officers, a ward section of 35 other ranks, and a transport section of 21 other ranks to pick up and transport the wounded.

The hospital was based on British practice with Canadian innovations, including improved tenting, ambulances, water trailers, and an acetylene gas lighting system. Many among the members of 10 CFH were veterans of previous tours in South Africa.

In South Africa a section of the unit accompanied the 2nd Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles into the western Transvaal. The remainder moved to Vaalbank, 60 kilometres away on the Lichtenberg blockhouse line. Here it received sick and wounded from the columns operating in the area.

This section of 10 CFH remained at Vaalbank until 18 June 1902 during which time it treated over a thousand patients, British, Boer and Black South African. 10 CFH ambulances evacuated patients for longer-term care to Klerksdorp. By all accounts, the 10th Canadian Field Hospital provided outstanding medical services during its stint in South Africa.

Canadian Victoria Cross Winners

Four members of Canadian units won the Victoria Cross (VC) during the South African War. This award was the British Empire's highest military decoration for gallantry.

The first winner of the Victoria Cross by a member of a Canadian unit was Sergeant A.H.L. Richardson of Strathcona's Horse. At Wolve Spruit on 5 July 1900, despite being mounted on a wounded horse himself, Richardson rode back through very heavy enemy fire to rescue a fellow Canadian who had been unhorsed and wounded. Sgt. Richardson was a member of the Northwest Mounted Police, as were many of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse, commanded by the legendary NWMP officer Sam Steele.

Three members of the Royal Canadian Dragoons, Lieutenants H.Z.C. Cockburn and R.E.W. Turner and Sergeant E.J. Holland, won the Victoria Cross during the desperate rear-guard action at Leliefontein on 7 November 1900. Both Cockburn and Turner had held off large groups of Boers at close range, allowing two Canadian field guns to escape capture. In the process, both officers were wounded, and Cockburn was captured.

As a general, Richard Turner would later command first the 3rd Canadian Brigade and then the 2nd Canadian Division during the First World War. Sergeant Holland kept several parties of Boers at bay with the fire from his Colt machine gun. With his gun jammed and in imminent danger of capture, he detached it from its carriage and carried it off to safety.

Two other Victoria Crosses were awarded to Canadians serving in Britain's Royal Army Medical Corps: Lieutenant H.E.M. Douglas for his conduct during the battle of Magersfontein in December 1899 and Lieutenant W.H.S. Nickerson for going to the assistance of a wounded comrade under fire at Wakkerstroom in April 1900.

Horses played a major role in each of the contingents of the Canadian units. Unfortunately many horses died enroute, while those that survived were too weak or ill for immediate service in South Africa. The Canadians had to settle for smaller Argentine horses for mounts and mules had to be used to haul gun carriages and wagons during the first months of action.

With the capability of speed and manoeuvrability, troops mounted on horses were a better match against the well mounted Boer fighters who were engaging in guerrilla style warfare. But even the well bred and well cared for horses of Lord Strathcona’s Horse has difficulty enduring the sea voyage and over one quarter of the regiment’s horses died, most from pneumonia.

Lord Strathcona’s Horse (RC) today

Since the Boer War, there has continued to be a close relationship between Armoured Corps soldiers and horses, particularly the Lord Strathcona’s Horse, the 8th Canadian Hussars and the Royal Canadian Dragoons, all of whom have replaced their horses with tanks and armoured carriers. Indeed today, the LDSH continues to maintain a mounted troop at their base in Edmonton which is used for ceremonial purposes.